‘People Public Private Partnerships’ for a Just Transition to a Decarbonized World

Sophie Punte, Managing Director Policy, We Mean Business Coalition

Sophie Punte (3rd from right) at the 35th Council of the European Green Party with, left to right: Kaspars Briškens (Progresīvie Latvia), Jean Lambert (Committee Member European Green Party) Aboubakar Soumahoro (Social Activist and Trade Unionist Italy – Côte d’Ivoire), Ricarda Lang (Co-Chair Bündis90/Die Grünen Germany), Ernest Urtasun (MEP and Vice-President Greens/EFA Group), Vula Tsetsi (Committee Member European Green Party).

Few need convincing that the climate crisis is real. We know we must act now to protect our future and that of our children. The challenge is to make the transition happen in a way that delivers for both people and the planet. During the 35th Council of the European Green Party in Riga early June, I was invited to bring a business perspective to a meeting on “Building a Green Future: Just Transition in Times of Crisis”. Inspired by the discussion, I wish to leave three suggestions with the hundreds of inspiring and motivated members of Green Parties across Europe.

1. Look for good business examples to inspire just transition policies

Greenwashing is very real and many companies are doing too little, too slowly. Powerful companies continue to lobby against climate policies. However, that doesn’t mean we should give up on all businesses as key players in tackling climate change. Instead, look out for businesses that are demonstrating climate leadership and give them a platform. Allow their insights to inspire policies in support of a just transition.

Here are some examples of companies that have embarked on the sustainability journey, aiming to bring the full workforce, suppliers and stakeholders along. Is any one of them perfect? No. But what they have in common is they have learnt to let go of perfection, accept that the road will be bumpy, and use what they have learnt to constantly improve and influence others along the way.

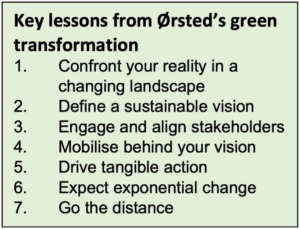

Denmark’s Ørsted transformed from a coal-intensive power generator with expanding oil and gas interests a decade ago, into one of the world’s largest renewable energy and offshore wind companies. This shift has resulted in improved financial performance and 86% CO2 reductions. Importantly, one of their seven lessons is to engage and align stakeholders: “Explain how the transformation creates value for each of your stakeholders, so they all have a stake in the process. If certain groups lose out, take the time to explain the reasons for change and listen to their views.”

The inspiring story of US carpet manufacturer Interface is beautifully told by Nathan Harvey’s movie Beyond Zero. CEO Ray Andersen in 1994 set his sights on making his business environmentally sustainable: in 2010 the company produced its first 100%-recycled nylon carpet, by 2021 it reached zero emissions. This would not have been possible without the inclusion of the full workforce, suppliers and communities that Interface interacts with.

Other companies are exploring a ‘regenerative economy’. It essentially means that as a company you give more to humanity and nature than you take from it, and thus contribute to restoring our ecosystems and societies. Patagonia tries this for cotton used in clothing, Natura & Co’s The Body Shop for cosmetics, and ACCIONA for infrastructure. The book ‘A European Just Transition for a Better World’ is a rich resource for more examples of this regenerative approach.

2. Set clear policies that give business only one direction of travel

Even companies that recognise the business opportunity of climate action, still need to make a business case. EU policies can stimulate ‘competitive sustainability’, which favors first movers and fast movers. For example, new low-carbon production processes for heavy industry increase production costs for steel by 20-30% and cement by 20-80%. This is where government co-investment and subsidies can help to create market demand for low carbon products until a tipping point is reached.

Contradictory policies stifle investments in low carbon solutions while leaving the door open for fossil fuels. The EU Taxonomy is a much needed development, creating clarity on what can be classified as ‘sustainable economic activities.’ However, including natural gas in there, even with strings attached, sends a confusing message about how serious the EU really is about reducing its dependency on fossil fuels. MEPs were right to object to it. Don’t be surprised if developing countries consider this a green light to invest in gas projects citing that the EU labels it sustainable.

Companies can use their voice and influence to support pro-climate policies that also support a just transition. CLG Europe, a founding Partner of We Mean Business Coalition, issued a letter signed by more than 160 companies with recommendations for the REPowerEU plan to European Commission President Von der Leyen. They call on the EU to accelerate the move away from fossil fuels but also to “ensure an inclusive and fair transition process, with clear attention to the growing pressures on cost of living, and access to decent work.” Hearing the positive voice from business can really help policy makers to set ambitious policy. This will be particularly important to build the case for a just transition. Several industry groups, for example steel and automotive, continue to use potential job losses as an argument to slow down the implementation of the EU Green Deal. A much stronger counter-narrative is needed, with the backing of business, focused on the jobs that will be created, especially if we move towards a circular economy. There is proof: a study by We Mean Business Coalition shows that implementing policies to end dependency on fossil fuels will cut household energy bills 28% or €409 in 2030. By 2035 consumers would spend roughly half as much on their energy costs, saving over €700 per year, compared to business as usual.

Mandatory disclosure by investors and corporations on targets, progress, risks and other climate-related information will help accelerate decarbonization and a just transition. We need one global reporting standard to ensure consistent reporting everywhere to make information comparable. The International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) can provide the global baseline, whilst the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) can add ambition. These two initiatives working in tandem will ensure that corporate reporting meets broader stakeholder needs and keeps companies on track with their science-based targets. An example of what can be added is the percentage of their investments that can be classified as ‘sustainable’ based on the EU Taxonomy – ACCIONA already does this. Political parties and policymakers can then make use of disclosed information to inform policy decisions.

3. Make it a condition that policies are green and social

This is the opportunity to shape a combined green and social policy for our future economy, which will also benefit progressive businesses. Policy makers should go about this creatively and communicate to people to get them on board. Let me illustrate this with a few examples. Climate Action Network give many more specific recommendations in a new report that highlights the importance of coordination on policies to maximize the social benefits of climate action.

Subsidizing electric vehicles right now is madness. EVs are already on the ‘S-curve’, plus it helps mostly the rich who can afford one. Why not put that money into EV charging infrastructure which will benefit all future EV drivers? Or into improving public transport that benefits citizens on low incomes? And don’t forget to communicate the social co-benefits to people, such as the correlation between EV uptake and improved air quality in European cities.

VAT exemptions for green products are popular with EU policy makers. I’m having solar panels installed on my roof right now, and I would still have gone ahead even without the 2,500 Euro subsidy, because return on investment is very good, especially in the context of rising energy prices. What if we don’t apply VAT exemptions for big houses but instead use this money to waive the student loan of an electrician technician on the condition that they work at least 3 years in the solar sector? Now you’re investing in jobs that we desperately need in the future and will benefit many more people than the one homeowner.

We could also look into how we can target support to help low-income families and tenants. Imagine a scheme that combines solar leasing with a gradual pay-off – this would substantially reduce upfront costs and increase electricity security for the rest of the panels’ 25-40 years working life. You could offer such a scheme to entire neighborhoods, creating economies of scale. Or install solar panels on school roofs and invest savings into raising teachers’ salaries as was done at a school in Arkansas.

People’s resistance to new solar parks and wind farms is growing. Local residents worry that the new infrastructure will affect their house values and even potentially their health, whilst missing out on any share of the profits. For example, in the Netherlands, close to 80% of the biggest solar parks built with Dutch taxpayers’ subsidies are in the hands of foreign investors. Yet the Dutch Climate Accord aims for 50% local ownership. The EU has proposed a one-year cap to award renewable energy permits but this could simply add fuel to the fire. How about putting a condition on government subsidies and the permit fast-track: at least 50% of the solar or wind farm must be locally owned?

It’s time for genuine collaboration between citizens, governments and businesses, or in other words, add another ‘P’ to: People Public Private Partnerships. Give people ownership, it’s the only just and realistic way to implement the EU Green Deal and to a decarbonized world.