Boosting EV take-up on the road to our global climate goals

Sophie Punte, We Mean Business Coalition and Michael Grubb, University College London Institute for Sustainable Resources

This article first appeared on Transport Policy Matters.

Most people planning to buy a new car in the next year are likely to be considering an electric one. For anyone not considering going electric, they may live to regret it. In just three years’ time, electric cars will likely beat petrol and diesel cars on cost, environmental impact and performance.

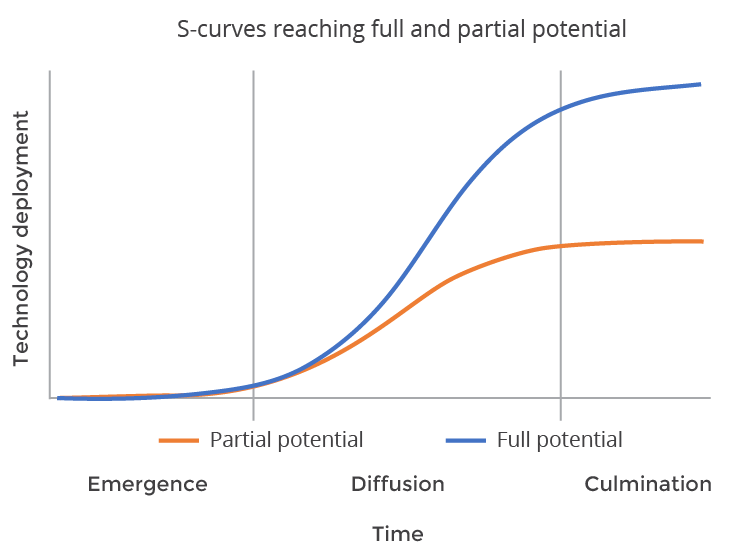

It feels like the progress on electric cars has moved at high speed over the last year, and data shows it’s only going to get even faster. This is because electric vehicle (EV) uptake is on what’s known as an ‘S-curve’ of growth. On every occasion this has happened in the past with other industrial transitions, governments, business and consumers have been taken by surprise.

Remember the years up to 2012, when we would proudly pull out our latest model of (for many) the Nokia mobile phone? Yet once smartphones arrived, we all switched rapidly without much thought. What you got with a smartphone for a fairly equivalent price made it worth it. The speed of the transition was phenomenal. We’ve seen similar patterns of S-curve growth with the switch from video rental to streaming. The telecommunications and film industry business models have been completely transformed.

So what can we expect in the car industry? A new study by the University College of London (UCL) in collaboration with the We Mean Business Coalition (WMB) shows that global EV sales have increased by an average of 41% per year since 2015. If growth follows this S-curve trajectory, all new cars sold could be electric by 2040.

In terms of the climate crisis – while this is positive news – we’ll need to push harder to get on track for halving emissions by 2030 and a net zero future by 2050. To achieve that, we need new passenger road vehicle sales to be 100% zero-emission by 2035.

Given the exponential growth so far, we may be tempted to hope that the market will take care of the problem itself. But we must not underestimate the measures needed to ensure a smooth path to 100% EVs. Current charging infrastructure is inadequate; there isn’t enough of it and it’s not seamlessly set up to make it easy enough for consumers. Also, EV purchase costs are still out of reach for many.

How do we deal with these challenges? Governments have a critical role to play, as featured in the report’s principal policy recommendations:

- Invest in infrastructure for reliable, seamless and publicly accessible charging.

- Commit to public procurement of EVs and incentivise private companies to do the same, for example through the Climate Group’s EV100 program.

- Help buyers overcome up-front EV purchase costs by stimulating leasing schemes and second-hand markets for EVs and batteries.

- Tighten emission standards and implement fiscal incentives to accelerate the simultaneous phasing out of the internal combustion engine.

- Invest in a simultaneous rapid transition to renewable power to ensure EVs are genuinely zero-emission.

And let’s make sure that we look beyond EVs because this is the decade of action. We must take a holistic approach to maximise the opportunities available including to:

- Futureproof legislation and infrastructure for a future where vans, light duty trucks and possibly even heavy trucks will go electric.

- Continue energy efficiency improvements, for both vehicles and for more efficient driving and route planning.

- Encourage appropriate use of cars and trucks alongside other transport modes; incentivise passenger travel by train, bike or foot, and efficient transportation of goods by rail or ship.

Moving on an EV s-curve will have deep implications, not limited to the clean vehicle and clean energy markets. Governmental action to stimulate a transition to EVs and renewable energy will therefore also require actions that go beyond the role that policy should take to stimulate these transitions. An upcoming ITF report points to three major areas that are worth greater consideration by policy makers and offers relevant recommendations on how to handle the challenges affecting them. These relate to changes in the demand for new materials and related supply chains, structural changes in government revenues from fuel taxes and impacts that a switch to EVs and renewables – as well a digital technologies – will have for jobs and changes in skillsets. Indeed, as we get excited about EVs, we should consider how to help transition workers from the traditional automotive industry into new jobs in EV manufacturing and beyond.

Taking action on all these fronts will ensure that the transition is achievable, sustainable and causes the least disruption to people as possible.

Our overall approach to car use could also make or break the success of the EV transition. What has become all too clear during the Covid-19 crisis is that collaboration between countries is essential to succeed. The same is true for the climate crisis. Emerging economies are an important market for second-hand cars including more polluting models. There is a risk is that these countries could soon be the dumping ground for petrol and diesel cars, keeping their emissions levels high with the associated localised air pollution effects. Tighter emission standards and preferably import bans for ICE vehicles and engines can reduce this risk.

The UCL/WMB report aims to give both business and policymakers worldwide the confidence to increase ambition in the transport sector and to boost the S-curve. Along with the ITF analysis on cleaner vehicles, it also helps to ensure that this technology transition will be resilient.

As we emerge from the Covid-19 crisis, governments can help business at key moments like the G7, G20 and COP26 to deliver clear, detailed policies to achieve their national targets in line with the Paris Agreement climate goals. As passenger road vehicles are responsible for 45% of global transport emissions, it is critical that we maximise their emissions reduction potential now. And EVs are not only better for the climate than petrol and diesel vehicles. They also improve human health through cleaner air and, if planned well, could increase jobs and growth. They can play an essential role in helping us build back better.