Fossil fuel phase out: from the policy fringe to centre stage

Andrew Prag, Managing Director for Policy

The chart is strikingly simple, as though drawn as part of a high school assignment – two swooping curves in opposite directions, crossing in the middle. One sinking quickly to zero and the other soaring to a high plateau.

But this is not a teenager’s sketch, it is the output of the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s sophisticated energy system modelling, depicting a global scenario for achieving net –zero CO2 emissions by 2050, in line with what science says is needed to avoid the most dangerous impacts of climate change.

Rapid growth in clean energy on the one hand and a rapid phasing out of fossil fuels on the other.

Chart 1: Energy demand in the IEA’s Net-zero emissions by 2050 Scenario

Source: IEA (2023), launch presentation for Net Zero Roadmap: A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach

In recent years, the world has seen tremendous and unprecedented growth in clean energy, as technology costs have fallen and clean options have become the economic first-best business case in many places. According to the IEA, growth rates of some technologies, such as solar PV and electric vehicles, are now reaching the levels required to ultimately achieve net –zero emissions globally by 2050.

Fossil fuels, though, have proved much more stubborn. Their proportion of the overall global energy mix has hovered for decades at close to 80%, despite the recent growth in clean energy. It has become clear that aiming policy and financial support towards clean energy growth alone is not enough. We cannot continue to ignore the fossil fuel side of the equation.

For a long time, the issue of addressing fossil fuels was at the fringe of international policy discussions. Policy makers and businesses alike were comfortable talking about promoting clean energy, but more reticent to address fossil fuels directly. Despite the centrality of fossil fuels to the fight against climate change, the term has barely featured in outputs of the UNFCCC. The Paris Agreement is completely silent on the topic, and the 2021 Glasgow Pact, while calling for a phase-down of coal-fired power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, stopped short of addressing fossil fuels overall.

But finally the ground is shifting. At COP27 in 2022, India led the call for a phase-out of all fossil-fuels, a historic shift in position from the world’s most populous nation. Other countries joined them, but fell short of securing multilateral agreement.

Still, a movement had begun, with fossil fuels shuffling from the sidelines into the centre of the policy stage. In May this year, the G7 countries did back the phase-out of fossil fuels in line with 1.5ºC trajectories, coupled with a rapid scaling of clean energy, despite difficult politics with the continued energy and cost of living crises continuing to play out in many of the G7 countries.

The G20 is always a more challenging forum for securing ambitious climate agreements, and all the more so with the context of global geopolitics in 2023. Meeting this year under India’s presidency, fresh from its call for fossil fuel phase-out at COP27, the group did secure agreement on a target for renewable energy globally and supporting efforts to accelerate energy efficiency. But language on fossil fuel phase out turned out to be a step too far.

As we move towards the COP28 UN climate conference in December this year, the IEA has taken account of this shifting international landscape, as well as a wide array of information on countries’ national policies and plans, as it updated its models. Something remarkable occurred – the 2023 World Energy Outlook, out this week, now projects that global fossil fuel demand will peak this decade, even under current plans and policies.

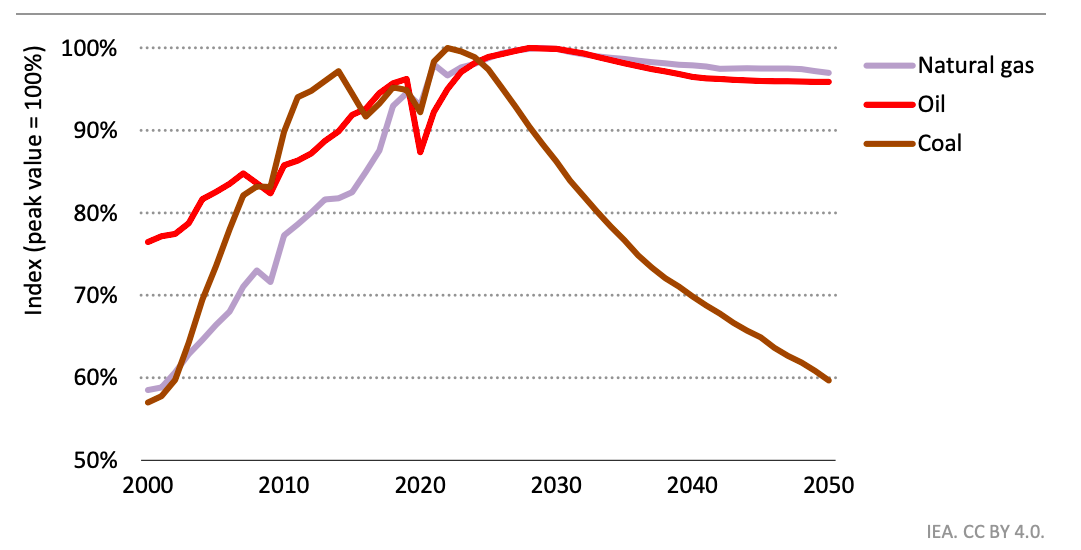

But what does this projection really mean, and is it enough? It is an important development and shows yet again that policy can really have impact in the real economy. But we should not be complacent about it, for two reasons. Firstly peaking fossil fuel use is not enough to drive the emissions reductions needed to hold warming to 1.5°C or even 2°C – what happens after the peak really matters. Compare the chart above with the one below showing how fossil fuel demand is projected to evolve under current policies and plans. The peak is there, yes, but the decline in demand following the peak is far from what is required, in particular for oil and gas.

Source: IEA World Energy Outlook 2023

Secondly, what will it really take to make this peak happen? A few years ago, such an imminent peak would only have been seen in an ambitious, climate-action-oriented scenario laying out what needs to be done to get towards climate goals. Now, it is almost “business as usual”.

Almost business as usual, but not quite. These projections assume that existing policies and plans come to fruition and are fully and effectively implemented. That is not a given in the messy world of policy implementation. As an example, just last month we saw the UK government rolling back its near-term policies while still keeping its longer-term commitment in place. So to make this peak happen – and to really set in motion a structural decline in emissions in line with climate goals – governments need to be pushed continually to strengthen, improve and align policies, by their most important stakeholders.

That is where the private sector comes in. Through our Fossil to Clean campaign, more than 130 demand-side companies, with combined revenue of nearly USD 1 trillion, are urging action by governments, financiers and the fossil fuel suppliers themselves to phase out fossil fuels as soon as possible. They are asking governments to not only make good on current policies, but also to push further for an accelerated transition. This campaign is only just beginning, and will grow and grow in coming years as an ever-stronger demand signal to governments, showing that businesses want governments to go further.

Fossil fuel phase-out needs to dance centre stage alongside policies to drive green energy. That has to start at COP28 later this year, with a clear multilateral agreement to phase-out fossil fuels in parallel with clean energy targets.

Let’s make the fossil peak a reality, and make it happen even sooner.